SESSIONS - Booklet and Infos

Wale Liniger, 2014

I have always liked stories. My first memories of listening take me back to my maternal grandmother. I remember her

as a master storyteller.

Sometimes she would read the stories out loud. After a while I knew the plots by heart, but the tales never got

boring as she identified the different characters by using a variety of vocal timbres in the dialogues. My

entertainment was the result of her articulations, which in turn depended very much on the moment: depending on

whether grandmother used her dentures or not, a character's voice sounded very differently. I preferred the

lisping sounds of the nighttime stories, a time when her dentures were submerged in a glass full of cleansing

saltwater. The resulting swishes of all the words containing the letters “the” and “s” brought some of the

unpredictable back to the known story. I still remember our laughter about all the strange sounding combinations of

letters and meaning. Sounds hold quite a bit of power, as our imagination will sketch the scenarios that create

them.

Other times the chronicles were about her life. I got to hear the narrative whenever time was right. Of course this

happened mainly throughout the day when her artificial teeth were in place: her pronunciations stayed on track, but

her stories were rather erratic, driven by time. As I got older I found grandmother's real stories to be increasingly attractive: she seemed to relive the moments she was talking

about, her narration became a performance. The accounts were about her life, and she let me be part of times and

places I would never see. The narrator has a lot of freedom in exploring the choices of presentation as long as the

core of the account remains intact. More and more I became drawn to the unveiling of personal truths.

My grandmother's talent in storytelling was twofold. She knew how to make a known story pattern attractive

again by playing with the inherent sounds and rhythms of her language; and she had accepted that intimate episodes

remain personal and stay tethered to the moment of experienced truth.

Such stories were hardly ever amusing, quite the opposite; they still shimmer in the recesses of my memory.

Such stories were hardly ever amusing, quite the opposite; they still shimmer in the recesses of my memory.

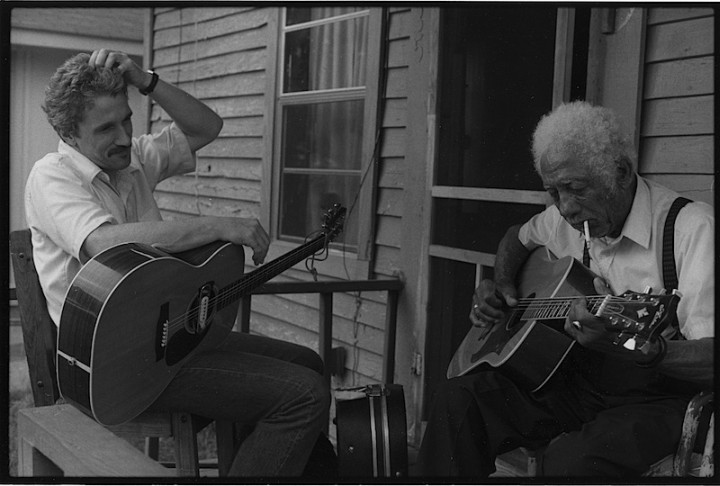

I've always understood the blues to be a story. In the beginning I focused almost exclusively on its musical

structures, such as sounds and rhythms. It all sounded simple enough for me to lose my fear of playing music. I

spent many years listening to recorded music, imitating its sounds, singing in a foreign language and fantasizing

about what could have been, alas, so far away. The blues seemed to invite minds and hearts like mine to a

conversation with the self.

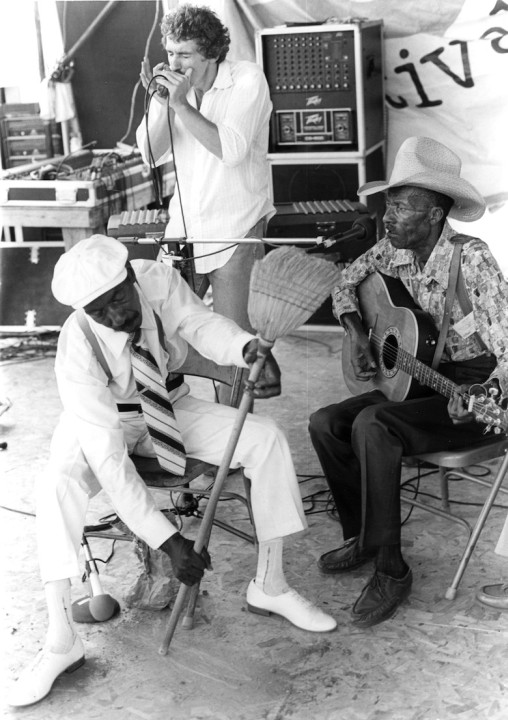

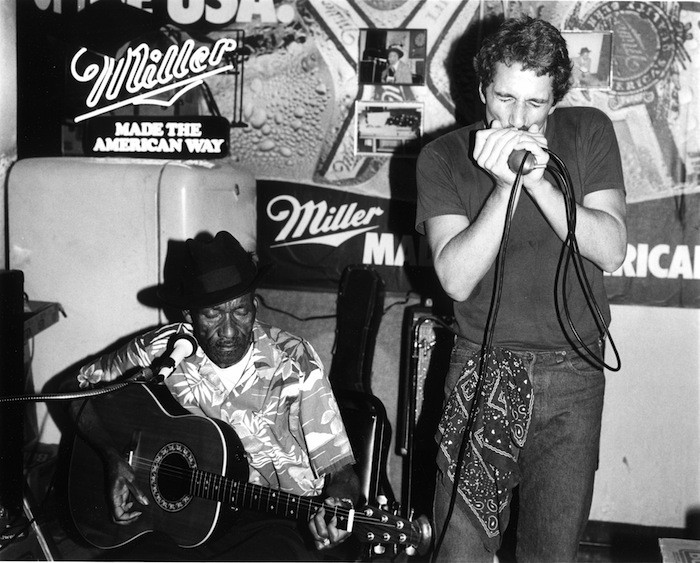

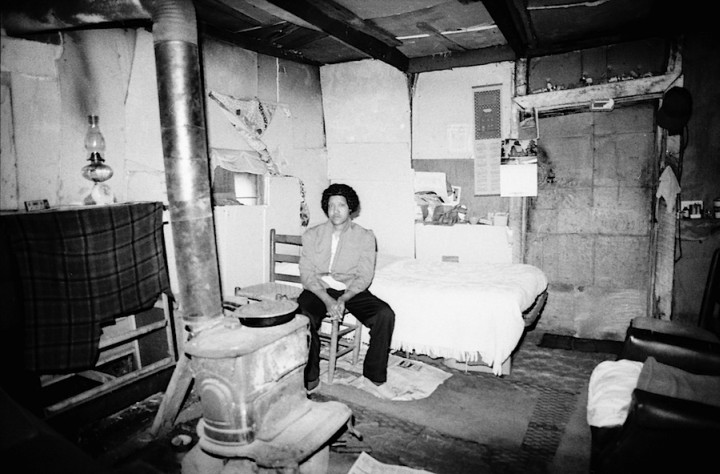

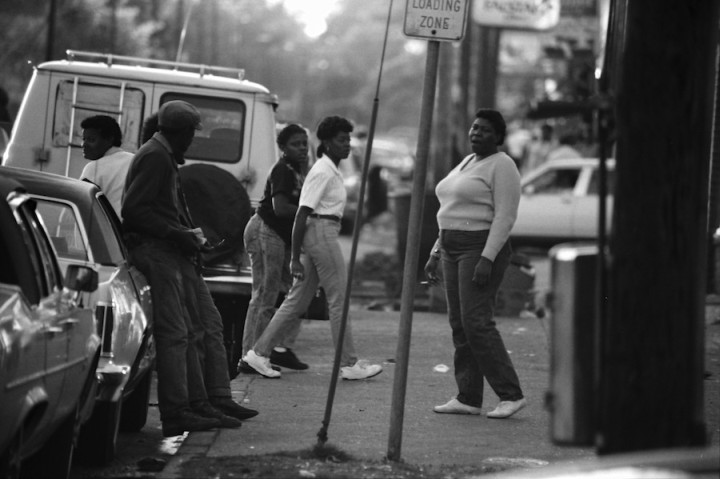

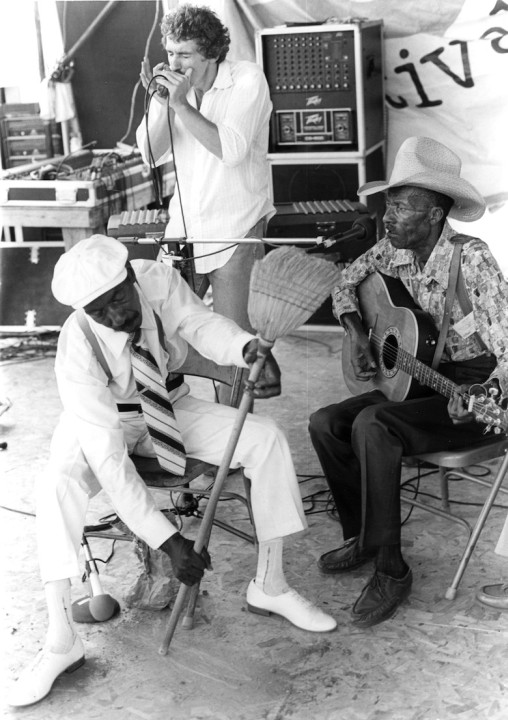

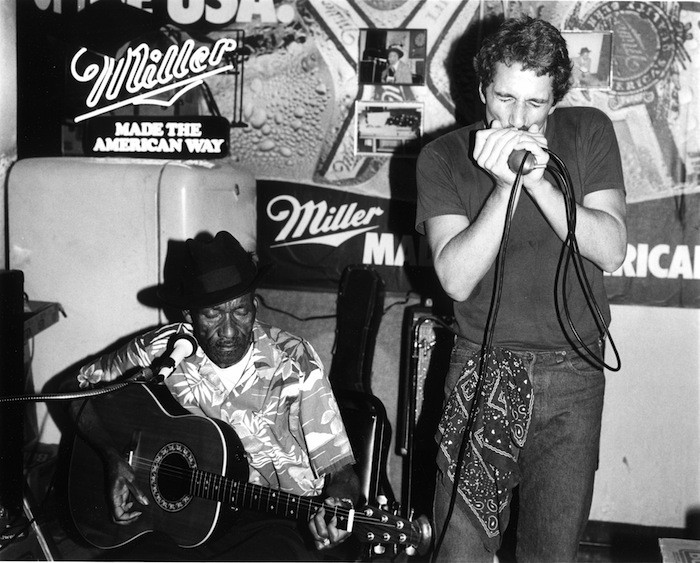

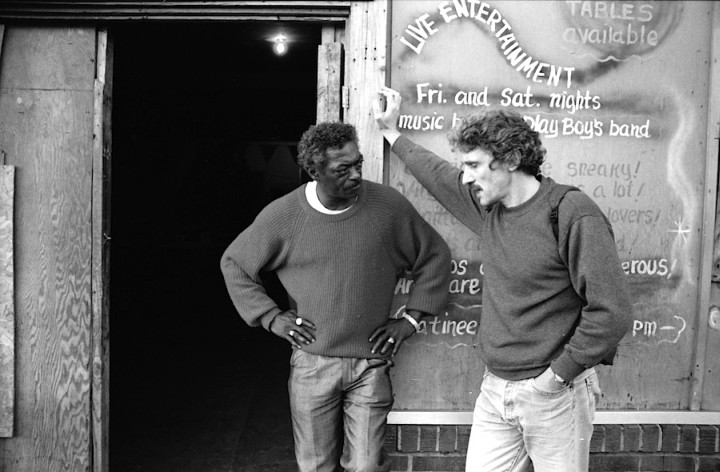

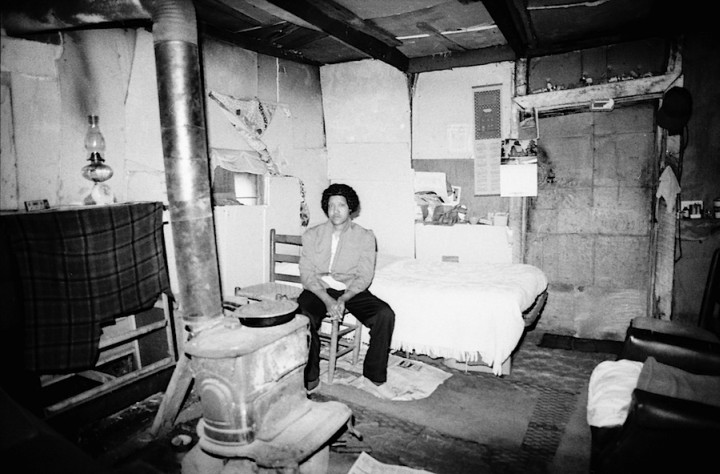

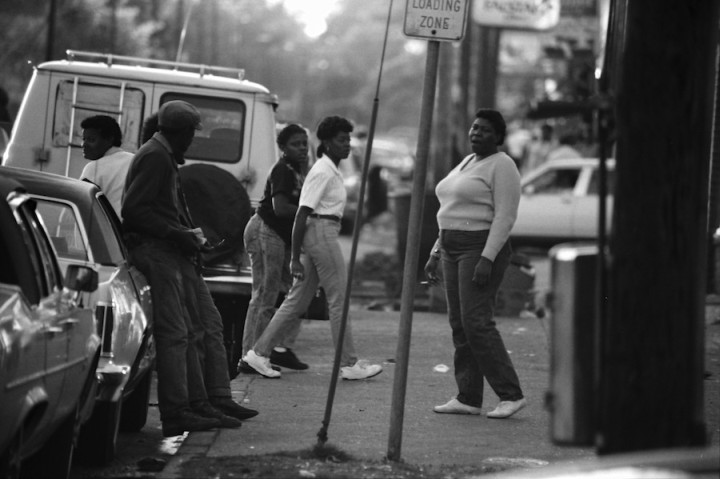

After moving to Mississippi in 1982 I became aware that my notion of the blues was a concoction of recorded music

and personal fantasies about being misunderstood. I had taken a voice of strength and turned it into a whiny

drizzle, lamenting romanticized hardships. My book-English got me through my workdays in the Blues Archive at the

University of Mississippi but failed me miserably when I was trying to understand what Delta bluesman James Son

Thomas wanted to tell me. I recognized his words in my translation, but quite often I did not understand the

emotional value of what he meant.

After moving to Mississippi in 1982 I became aware that my notion of the blues was a concoction of recorded music

and personal fantasies about being misunderstood. I had taken a voice of strength and turned it into a whiny

drizzle, lamenting romanticized hardships. My book-English got me through my workdays in the Blues Archive at the

University of Mississippi but failed me miserably when I was trying to understand what Delta bluesman James Son

Thomas wanted to tell me. I recognized his words in my translation, but quite often I did not understand the

emotional value of what he meant.

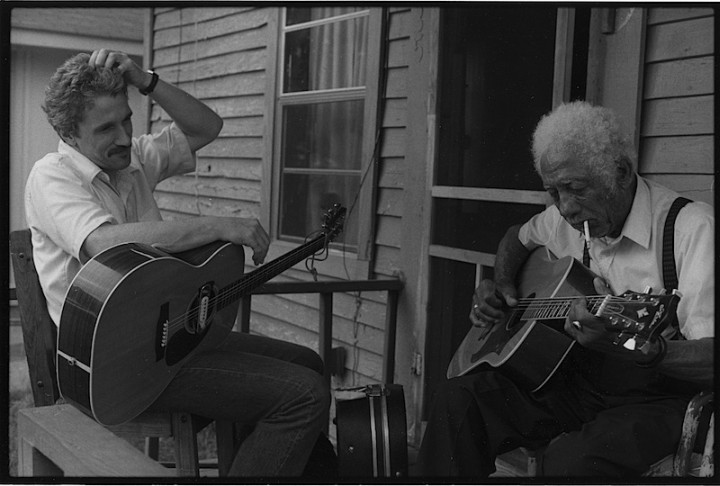

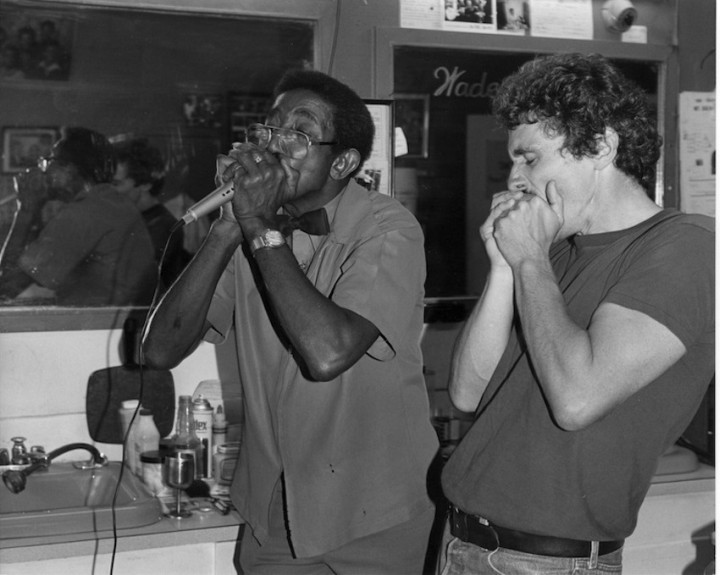

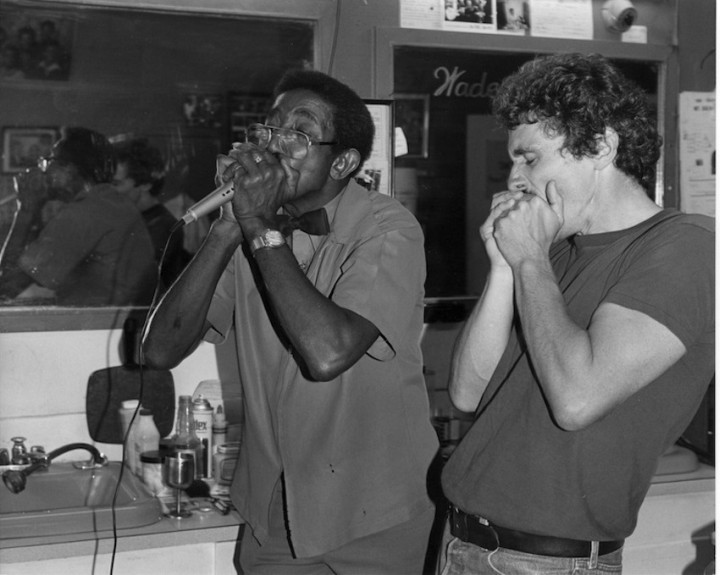

One day James Son Thomas mentioned that I needed to sing the blues in my own voice. In

translation this statement told me that I did not need to change the sound and articulation of my voice in order to

sing the blues. This put my mind at ease, as I was sure that I had not assumed a different character when singing

the blues. But I was still interpreting and reciting a recorded composition, somebody else's story.

One day James Son Thomas mentioned that I needed to sing the blues in my own voice. In

translation this statement told me that I did not need to change the sound and articulation of my voice in order to

sing the blues. This put my mind at ease, as I was sure that I had not assumed a different character when singing

the blues. But I was still interpreting and reciting a recorded composition, somebody else's story.

Thomas' claim that I needed to use my own voice was far more challenging than dealing

with sounds and phrasing. The elder bluesman demanded that the words reflected my own

experiences. And, similar to my grandmother's impromptu stories, the blues suddenly became much more

intimate, often very troubling.

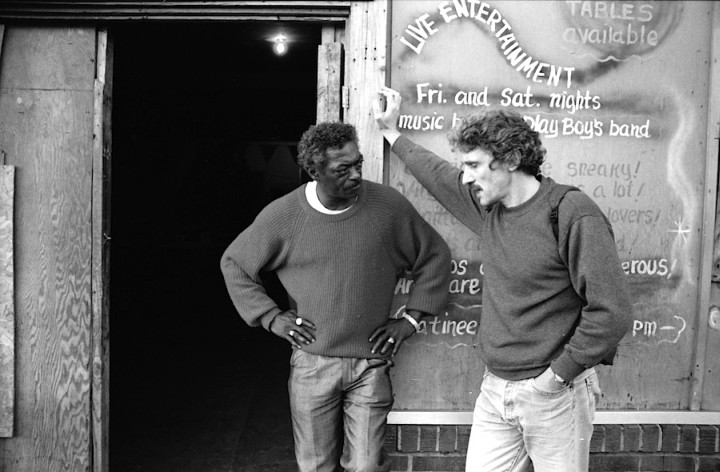

Learning a foreign language helps in our exchanges across the language barrier. I have noticed that I may know what

a word means in its translated form, but more often than not I am not sure what I should feel. It is important to me

how a word resonates within. So far, many of my oldest responses remain attached to the word-sounds of my mother

language, Swiss German. Living in two different cultures has brought me to a somewhat disquieting insight: memories

of my formative years often stood in the way of a more intimate embrace and acceptance of my host-culture. I have

never let go of my original intention to visit America for a brief time only. But I stayed. In hindsight I would

describe myself as an observer, still.

I did not arrive at this insight on my own. My head was full with information when I arrived in the American

southland. “Book knowledge” had seduced me to believe

that the Blues was something rather abstract, conducive to a myriad of interpretations, even solutions, if only I

thought long and hard about it. Yet all the older blues people kept insisting that the Blues is,

always is. And so, over the years, I slowly began dismantling the stereotypes I had attached to this

enigmatic, cultural voice. I am not sure how far I will get, but I will accept what Time allows me to hold on

to.

that the Blues was something rather abstract, conducive to a myriad of interpretations, even solutions, if only I

thought long and hard about it. Yet all the older blues people kept insisting that the Blues is,

always is. And so, over the years, I slowly began dismantling the stereotypes I had attached to this

enigmatic, cultural voice. I am not sure how far I will get, but I will accept what Time allows me to hold on

to.

Part of my confusion might reside in the word “blues.” When I consult dictionary and thesaurus, I find plenty of

connotations referring to the metaphoric use of the color “blue,” I read of its symbolic values that range from

infinite to demonic (particularly in its plural form of “the blues”), from transparent to sad, and further into the

maelstrom. I suspect the use of “blue” in the writings of some German poets of the romantic period had influenced my

take on the musical voice as well. Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff and Novalis come to mind.

Part of my confusion might reside in the word “blues.” When I consult dictionary and thesaurus, I find plenty of

connotations referring to the metaphoric use of the color “blue,” I read of its symbolic values that range from

infinite to demonic (particularly in its plural form of “the blues”), from transparent to sad, and further into the

maelstrom. I suspect the use of “blue” in the writings of some German poets of the romantic period had influenced my

take on the musical voice as well. Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff and Novalis come to mind.

On a very basic level, the long-outdated fragment playing the reals tells me more than playing the blues. According to the late bluesman George “Wild Child” Butler, playing

the reals referred to what I deem as true, the sum of my experienced realities. Something is real when I experience it, when I am affected by

it. Such moments help in locating my self in the context of life as they invoke my ethical memory as well. And

ultimately those experiences make up my life. Butler was not alone with his observation: bluesmen Frank Davis from

Moorhead (Mississippi) and Jerry “Kool-Aid” Doss from Columbus (Mississippi) had very similar explanations. I do not

view this insight as a definition of the blues, but it points to an intriguing possibility.

On a very basic level, the long-outdated fragment playing the reals tells me more than playing the blues. According to the late bluesman George “Wild Child” Butler, playing

the reals referred to what I deem as true, the sum of my experienced realities. Something is real when I experience it, when I am affected by

it. Such moments help in locating my self in the context of life as they invoke my ethical memory as well. And

ultimately those experiences make up my life. Butler was not alone with his observation: bluesmen Frank Davis from

Moorhead (Mississippi) and Jerry “Kool-Aid” Doss from Columbus (Mississippi) had very similar explanations. I do not

view this insight as a definition of the blues, but it points to an intriguing possibility.

Playing the reals refers to an individual's experience, but I am never sure if the

narrator is that particular individual or not. A storyteller hopes for a sympathetic resonance in the audience, s/he

relies on the experiences and imagination of the listener. There has to be an inherent and

recognizable human component to the “moral of the story.”

Playing the reals refers to an individual's experience, but I am never sure if the

narrator is that particular individual or not. A storyteller hopes for a sympathetic resonance in the audience, s/he

relies on the experiences and imagination of the listener. There has to be an inherent and

recognizable human component to the “moral of the story.”

I have discovered that I am more likely to overuse pathos when performing somebody else's story, probably

because I am interpreting another person's words. Those words have no direct connection to my reality and

remain by and large abstract. When working with my experiences I am much more careful with the presentation: I do

not want to elicit pity, I do not want to sound whiny, quite the opposite. I want to show that I can accept

misfortune, especially when my own screw-up lies at its core. Stayin' cool comes to

mind.

I make a distinction between having the blues and playing the blues. I

need breath and strength in order to play. When I'm struggling with what haunts me, I hardly have the physical

and mental control to guide the story. Time is of essence. Only Time will tell if the experience will live on in a

story.

I do not seek refuge in the idea that Time heals. There are wounds that don't close,

holes that don't fill. They exist for a reason. I call them time-markers. During the project SESSIONS it became

clear to me that I can fly across the ocean (Move Across the Deep Blue Sea), but that I have not yet been able to

overcome the division within: after living half of my life in the American south I am still confused about where I

want to belong. The answer is not as easy as in home is where your roots are, or home is where you find a Wi-Fi spot. When in Switzerland I feel out of sync between my

remembered Time and the Now. And in the Southland I am told that I will never be Southern as I am not from there.

Does one have to belong anywhere? I am not sure that there is a generic answer as the question continues to circle

back to this enigmatic sense of being, the blues.

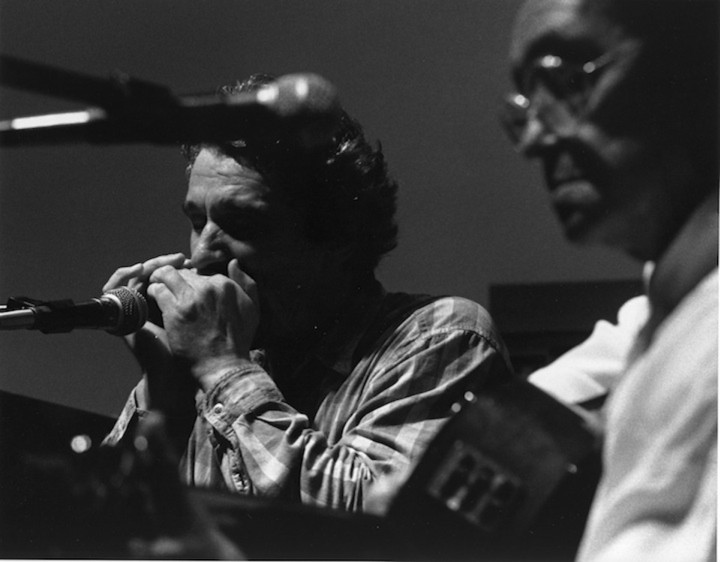

SESSIONS is a collection of stories pointing to remembered insights. While the voice alternates between solo and

band performance, I recognize and accept the stories as part of my life (the storyteller remains the same, the

sounds change). Most of the songs have accompanied me as fragments for quite some time. SESSIONS gave me the

opportunity to revisit times I thought important enough to remember.

Railroad switchyards are places where existing train compositions are examined in regards to their destinations,

newly composed and sent on. In a similar way, a session (a moment of relevant interaction) often leads to a

compromise, a new formulation of future possibilities. Of course the most intimate session I can have is my inner

dialogue with the self, a place that wants to shine and remain invisible all at once. Sessions are always moments of

experience.

Although I have been living in the American South for more than half of my life, I still feel Swiss. Thus the blues

as a musical form remains an exotic voice, whereas the blues as a personal narrative doesn't seem to be overly

mysterious, quite the opposite. The blues connects us with something that is an integral part of who we are: when

you listen to “Intersections” and “Casablanca Tango” you will hear musical strains that have been part of Swiss

culture for many years.

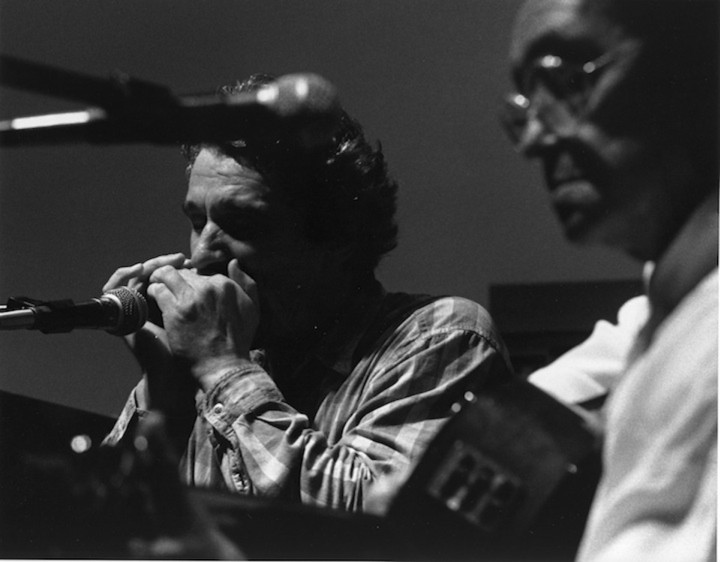

As I usually perform solo, playing with the band “The Alligators” forced me to leave some of my comfort zones and

make the necessary adjustments. Our biographies not only reveal that we were born in Switzerland, but also that we

approach the music from our respective musical vantage points. We are equally aware that blues music lies at the

core of what we enjoy playing. The project SESSIONS not only shows that we all had to make the necessary compromises

in order to play together, but that we all tried to keep our individualistic interpretations as well. The goal was

not to create a cookie-cutter blues band sound, but to let the music happen and see what comes of it, when we

surrender to our intimacy and simply play what we feel the blues to be.

As I usually perform solo, playing with the band “The Alligators” forced me to leave some of my comfort zones and

make the necessary adjustments. Our biographies not only reveal that we were born in Switzerland, but also that we

approach the music from our respective musical vantage points. We are equally aware that blues music lies at the

core of what we enjoy playing. The project SESSIONS not only shows that we all had to make the necessary compromises

in order to play together, but that we all tried to keep our individualistic interpretations as well. The goal was

not to create a cookie-cutter blues band sound, but to let the music happen and see what comes of it, when we

surrender to our intimacy and simply play what we feel the blues to be.

I arrived at the stories through my experiences; real living (experience) happened before there was the abstract

(story). Personal experience lies at the foundation of a story with emotional memory; that memory remains tied to

the individual. The abstract alone is devoid of the memory, it is an intellectual concept. One of our difficulties

was to understand our respective platforms in regards to the stories (real & abstract) and to accept what we

couldn't change.

I arrived at the stories through my experiences; real living (experience) happened before there was the abstract

(story). Personal experience lies at the foundation of a story with emotional memory; that memory remains tied to

the individual. The abstract alone is devoid of the memory, it is an intellectual concept. One of our difficulties

was to understand our respective platforms in regards to the stories (real & abstract) and to accept what we

couldn't change.

Working on SESSIONS made me undeniably aware how outdated my knowledge of Switzerland actually has become, and how

incomplete my understanding of the American south will remain. Memories are not always on my side, au contraire;

more and more I find them to be stumbling blocks when being in either one of the two cultures. In my native country

they confine me to a time long gone, and in the Southland they keep me from belonging. The blues refers to such

divisions, but whether I consider them to be restricting or liberating is up to me. There is no way to by-pass the

self when dealing with the reals.

Working on SESSIONS made me undeniably aware how outdated my knowledge of Switzerland actually has become, and how

incomplete my understanding of the American south will remain. Memories are not always on my side, au contraire;

more and more I find them to be stumbling blocks when being in either one of the two cultures. In my native country

they confine me to a time long gone, and in the Southland they keep me from belonging. The blues refers to such

divisions, but whether I consider them to be restricting or liberating is up to me. There is no way to by-pass the

self when dealing with the reals.

The most surprising insight had to do with my reactions to living in the two different cultures (Switzerland and

America). Despite the danger of being misunderstood I want to sketch this personal issue: when I sing my stories for

a Swiss audience, I wonder whether the listener actually understands my English (it is not my

book-English anymore, living for over thirty years in the south has brought about some changes). On the other hand,

when I perform for an audience in the Southland I wonder and worry about what they think.

Depending on whether the listener is a Southerner, or a Swiss, my music feels very different to me. I have carried

such a discord within ever since I moved to the American Southland.

Such stories were hardly ever amusing, quite the opposite; they still shimmer in the recesses of my memory.

Such stories were hardly ever amusing, quite the opposite; they still shimmer in the recesses of my memory. After moving to Mississippi in 1982 I became aware that my notion of the blues was a concoction of recorded music

and personal fantasies about being misunderstood. I had taken a voice of strength and turned it into a whiny

drizzle, lamenting romanticized hardships. My book-English got me through my workdays in the Blues Archive at the

University of Mississippi but failed me miserably when I was trying to understand what Delta bluesman James Son

Thomas wanted to tell me. I recognized his words in my translation, but quite often I did not understand the

emotional value of what he meant.

After moving to Mississippi in 1982 I became aware that my notion of the blues was a concoction of recorded music

and personal fantasies about being misunderstood. I had taken a voice of strength and turned it into a whiny

drizzle, lamenting romanticized hardships. My book-English got me through my workdays in the Blues Archive at the

University of Mississippi but failed me miserably when I was trying to understand what Delta bluesman James Son

Thomas wanted to tell me. I recognized his words in my translation, but quite often I did not understand the

emotional value of what he meant. One day James Son Thomas mentioned that I needed to sing the blues in my own voice. In

translation this statement told me that I did not need to change the sound and articulation of my voice in order to

sing the blues. This put my mind at ease, as I was sure that I had not assumed a different character when singing

the blues. But I was still interpreting and reciting a recorded composition, somebody else's story.

One day James Son Thomas mentioned that I needed to sing the blues in my own voice. In

translation this statement told me that I did not need to change the sound and articulation of my voice in order to

sing the blues. This put my mind at ease, as I was sure that I had not assumed a different character when singing

the blues. But I was still interpreting and reciting a recorded composition, somebody else's story.

that the Blues was something rather abstract, conducive to a myriad of interpretations, even solutions, if only I

thought long and hard about it. Yet all the older blues people kept insisting that the Blues is,

always is. And so, over the years, I slowly began dismantling the stereotypes I had attached to this

enigmatic, cultural voice. I am not sure how far I will get, but I will accept what Time allows me to hold on

to.

that the Blues was something rather abstract, conducive to a myriad of interpretations, even solutions, if only I

thought long and hard about it. Yet all the older blues people kept insisting that the Blues is,

always is. And so, over the years, I slowly began dismantling the stereotypes I had attached to this

enigmatic, cultural voice. I am not sure how far I will get, but I will accept what Time allows me to hold on

to. Part of my confusion might reside in the word “blues.” When I consult dictionary and thesaurus, I find plenty of

connotations referring to the metaphoric use of the color “blue,” I read of its symbolic values that range from

infinite to demonic (particularly in its plural form of “the blues”), from transparent to sad, and further into the

maelstrom. I suspect the use of “blue” in the writings of some German poets of the romantic period had influenced my

take on the musical voice as well. Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff and Novalis come to mind.

Part of my confusion might reside in the word “blues.” When I consult dictionary and thesaurus, I find plenty of

connotations referring to the metaphoric use of the color “blue,” I read of its symbolic values that range from

infinite to demonic (particularly in its plural form of “the blues”), from transparent to sad, and further into the

maelstrom. I suspect the use of “blue” in the writings of some German poets of the romantic period had influenced my

take on the musical voice as well. Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff and Novalis come to mind. On a very basic level, the long-outdated fragment playing the reals tells me more than playing the blues. According to the late bluesman George “Wild Child” Butler, playing

the reals referred to what I deem as true, the sum of my experienced realities. Something is real when I experience it, when I am affected by

it. Such moments help in locating my self in the context of life as they invoke my ethical memory as well. And

ultimately those experiences make up my life. Butler was not alone with his observation: bluesmen Frank Davis from

Moorhead (Mississippi) and Jerry “Kool-Aid” Doss from Columbus (Mississippi) had very similar explanations. I do not

view this insight as a definition of the blues, but it points to an intriguing possibility.

On a very basic level, the long-outdated fragment playing the reals tells me more than playing the blues. According to the late bluesman George “Wild Child” Butler, playing

the reals referred to what I deem as true, the sum of my experienced realities. Something is real when I experience it, when I am affected by

it. Such moments help in locating my self in the context of life as they invoke my ethical memory as well. And

ultimately those experiences make up my life. Butler was not alone with his observation: bluesmen Frank Davis from

Moorhead (Mississippi) and Jerry “Kool-Aid” Doss from Columbus (Mississippi) had very similar explanations. I do not

view this insight as a definition of the blues, but it points to an intriguing possibility. Playing the reals refers to an individual's experience, but I am never sure if the

narrator is that particular individual or not. A storyteller hopes for a sympathetic resonance in the audience, s/he

relies on the experiences and imagination of the listener. There has to be an inherent and

recognizable human component to the “moral of the story.”

Playing the reals refers to an individual's experience, but I am never sure if the

narrator is that particular individual or not. A storyteller hopes for a sympathetic resonance in the audience, s/he

relies on the experiences and imagination of the listener. There has to be an inherent and

recognizable human component to the “moral of the story.”

As I usually perform solo, playing with the band “The Alligators” forced me to leave some of my comfort zones and

make the necessary adjustments. Our biographies not only reveal that we were born in Switzerland, but also that we

approach the music from our respective musical vantage points. We are equally aware that blues music lies at the

core of what we enjoy playing. The project SESSIONS not only shows that we all had to make the necessary compromises

in order to play together, but that we all tried to keep our individualistic interpretations as well. The goal was

not to create a cookie-cutter blues band sound, but to let the music happen and see what comes of it, when we

surrender to our intimacy and simply play what we feel the blues to be.

As I usually perform solo, playing with the band “The Alligators” forced me to leave some of my comfort zones and

make the necessary adjustments. Our biographies not only reveal that we were born in Switzerland, but also that we

approach the music from our respective musical vantage points. We are equally aware that blues music lies at the

core of what we enjoy playing. The project SESSIONS not only shows that we all had to make the necessary compromises

in order to play together, but that we all tried to keep our individualistic interpretations as well. The goal was

not to create a cookie-cutter blues band sound, but to let the music happen and see what comes of it, when we

surrender to our intimacy and simply play what we feel the blues to be. I arrived at the stories through my experiences; real living (experience) happened before there was the abstract

(story). Personal experience lies at the foundation of a story with emotional memory; that memory remains tied to

the individual. The abstract alone is devoid of the memory, it is an intellectual concept. One of our difficulties

was to understand our respective platforms in regards to the stories (real & abstract) and to accept what we

couldn't change.

I arrived at the stories through my experiences; real living (experience) happened before there was the abstract

(story). Personal experience lies at the foundation of a story with emotional memory; that memory remains tied to

the individual. The abstract alone is devoid of the memory, it is an intellectual concept. One of our difficulties

was to understand our respective platforms in regards to the stories (real & abstract) and to accept what we

couldn't change. Working on SESSIONS made me undeniably aware how outdated my knowledge of Switzerland actually has become, and how

incomplete my understanding of the American south will remain. Memories are not always on my side, au contraire;

more and more I find them to be stumbling blocks when being in either one of the two cultures. In my native country

they confine me to a time long gone, and in the Southland they keep me from belonging. The blues refers to such

divisions, but whether I consider them to be restricting or liberating is up to me. There is no way to by-pass the

self when dealing with the reals.

Working on SESSIONS made me undeniably aware how outdated my knowledge of Switzerland actually has become, and how

incomplete my understanding of the American south will remain. Memories are not always on my side, au contraire;

more and more I find them to be stumbling blocks when being in either one of the two cultures. In my native country

they confine me to a time long gone, and in the Southland they keep me from belonging. The blues refers to such

divisions, but whether I consider them to be restricting or liberating is up to me. There is no way to by-pass the

self when dealing with the reals.